Recently, my friend Jonathan Dodson published a post on the failure of the missional church, which gave rise to some thoughts on the current state of this term. My growing sense of discomfort with the term has been increased by the its use on Twitter.

Recently, my friend Jonathan Dodson published a post on the failure of the missional church, which gave rise to some thoughts on the current state of this term. My growing sense of discomfort with the term has been increased by the its use on Twitter.

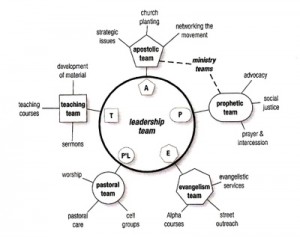

The term “missional” has been floating around since the 70s, but exploded in popularity over the past five years. It’s generally credited to Lesslie Newbigin, who realized the need to apply the missionary principles he learned in India to the Western Church. Over the last few years the term has popularized by writers like Darrell Guder, Alan Hirsch, and Ed Stetzer.

Like any trendy terminology, it’s only a matter of time before a term is co-opted by a certain group to mean whatever they want it to mean. Some trendy church words from the past few decades include “reformed,” “nations,” “life-giving,” “seeker-sensitive,” “purpose-driven,” “emergent,” and “culturally relevant.” Each of these terms are birthed out of a sense of burden from an individual or group to make up for something missing in the church. Over time, the terms are institutionalized and their meaning and scope are limited. Perhaps this has already happened to missional.

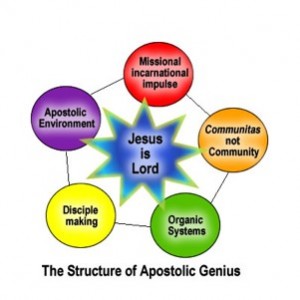

A quick and dirty definition of missional church might be:

1. A church who recognizes that God is on a mission, and that they are part of it.

2. A church that sees themselves as “sent” into an existing culture, and seeks to live out God’s kingdom within the reality of that culture.

3. A church that is concerned about God’s whole mission, both redeeming lost souls and restoring broken systems.

Across denominations, churches have pounced on the term missional live a pack of starved animals. Perhaps this comes out a genuine recognition that the church is being increasingly marginalized by the Western culture. Perhaps it grows out of a sense of purposeless. If churches turn their minds to the seeking their place in the mission of God, this can only be a good thing, right?

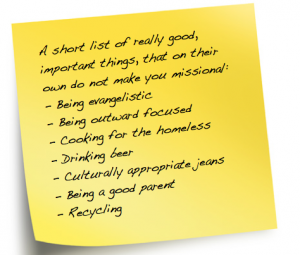

So how is the term missional being misused? Here’s some examples:

USE: Churches who place a high value on evangelism renaming their existing style of outreach as missional.

MISUSE: Doing so without questioning the effectiveness of their methods, or any long term disadvantages they may create for the ongoing mission of God.

USE: Individuals focused on social justice issues rebranding their pet causes as missional.

MISUSE: Focusing on broken systems at the expense of broken individuals.

USE: Movements focused on particular structures-ie “traditional family,” right or left economic models, patriarchy, feminism, environmentalism, etc- slap missional on top of their agenda.

MISUSE: Promoting a structure that is rooted in a culture, trend or time period, without questioning its place in the kingdom of God.

If the missional church fails, it is not because there is a problem with the theology of joining God’s mission. It’s because we’re trying to force God into our mission.

Perhaps some good questions to ask before applying the word missional on something are:

– If Jesus were physically here right now, would he be involved in this?

– How does this action help bring individuals and systems within this particular culture closer to God’s ideal?

– Does this action forward the mission of God, or just solve my immediate need?

– If this effort succeeds, who will receive the glory? Who will suffer?

– Where does this action fit into the overarching story of God and his people?

Related Posts:

Tweets

Tweets